‘Festina lente’ was the motto of Aldo Manuzio’s printing business in Venice. It translates nicely to ‘hurry slowly’ which is an elegant and appropriate motto for a publisher and printer who focused on quality and a scholarly approach to printing.

When Johannes Gutenberg invented the mechanical movable-type printing press in Mainz, Germany in the middle years of the 15th century he created a phenomenon that ignited a printing and information revolution that spread rapidly across Europe.

The city of Venice was ideally placed to become an important centre of printing. By 1500 there were at least 200 printing presses operating in the historic centre ‘centro storico’ of the city. Venice had a magnetic appeal for printers and publishers, the city was wealthy, the Venetians were tolerant (relatively speaking) and there was a high level of literacy, which meant a high demand for books, pamphlets and leaflets. Add to this potent mix the Venetians liberal approach to different religions and cultures and a multilingual population demanding books in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and Italian and one can see an inevitable boom in the printing and publishing world centred on Venice. Venice’s pre-eminence as a European city of trade and controller of trade routes across the Eastern Mediterranean guaranteed printers the raw materials and the distribution channels that they needed to make and sell their books. By the 1550s it is estimated that Venice was printing around 30% of all the books published in Europe.

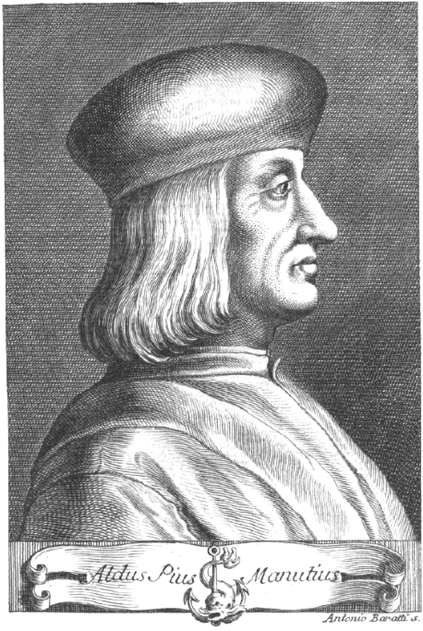

The Republic of Venice always supported business and trade first. Printers arrived from Rome and Austria to practise their trade in an open-minded city. This was a city that kept the Pope at arm’s length, making Venice a perfect home for educated and independent thinkers like Aldo Manuzio, whose name was often ‘Latinised’ as was the fashion at the time to Aldus Manutius. Manutius arrived in Venice from Rome attracted by a liberal attitude to publishing. Manutius was a scholar and humanist. He founded The Aldine Press in 1494 with a focus on Greek and Latin masterpieces. He published Greek classics including Aristophanes, Plato and Aristotle. From the Roman canon he published Virgil, Horace and Cicero. He also published the masters of early Italian literature including Dante Alighieri and Francesco Petrarca. Aldus Manutius was a man of intellect and taste. He was also extremely influential. When Manutius selected a manuscript or incunabula (early printed book) for publishing he was effectively deciding what the book-buying public were going to read. Curiously the John Rylands Library, Manchester University (where I did my Master’s in History of Art) now houses the most complete collection of Aldine editions in Europe.

Manutius was also an innovator, developing a simple type face which was the forerunner of the ‘italic’ typeface still in use today. He devised the shape and curve of the individual letters that are now regarded as one of our ‘standard’ modern typefaces.

The other extraordinary innovation that Manutius pioneered was the ‘libelli portatiles in formam enchiridii’ meaning ‘portable little books in the form of a manual’. These were small books, similar to modern paperbacks. Sometimes knows as an octavo (‘in eight’) edition because each large sheet of folio paper was folded three times to create eight pages (rather than just two large pages). This allowed for cheaper printing costs and longer print runs. A typical print run of an ‘octavo’ was 1000 copies, whilst larger traditional folio books were usually printed in batches of about 100. The ‘octavo’ was small and light and easily portable. It revolutionised reading habits. These compact little books could be carried easily, popped in a pocket or even a lady’s handbag. No more waiting in a public place with nothing to do – just open up your little book and refresh your memory on Cicero’s orations. Perfect!

The Aldine Press continued in Venice for three generations from 1494 to 1598 producing over 600 works. The printer’s device of the dolphin and anchor is well known in publishing circles. The dolphin signified speed in execution and delivery whilst the anchor indicated firmness and consideration. Manutius used the Latin motto ‘festina lente’ meaning to hurry slowly which implies a methodical and thorough approach to his work. Aldus had a workshop and printing office at San Polo, on the corner of Calle del Pistor. He became quite well known in Venice and visitors would call into the printing shop and interrupt Manutius at his work. Eventually Manutius put up a sign which said,

“Whoever you are, Aldus asks you again and again what it is you want from him. State your business briefly and then immediately go away”

Aldus Manutius (profile), Printer’s mark, William Caxton & Manutius, Tiffany Glass, Pequot Library, USA

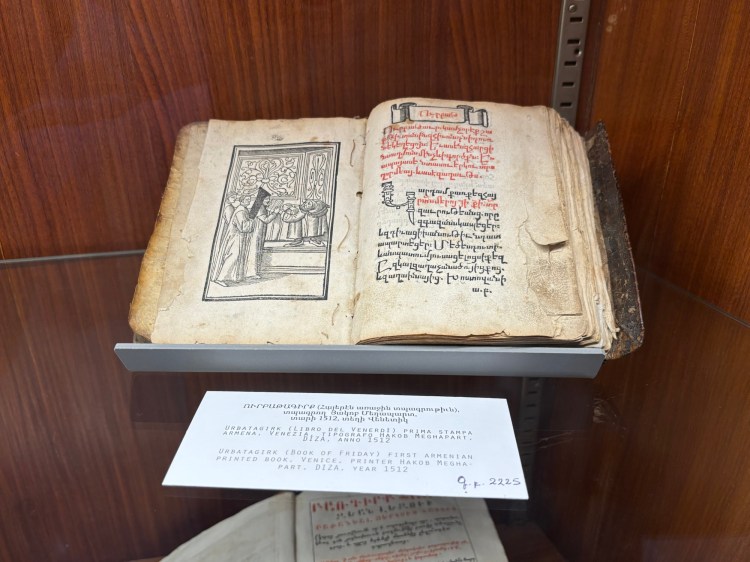

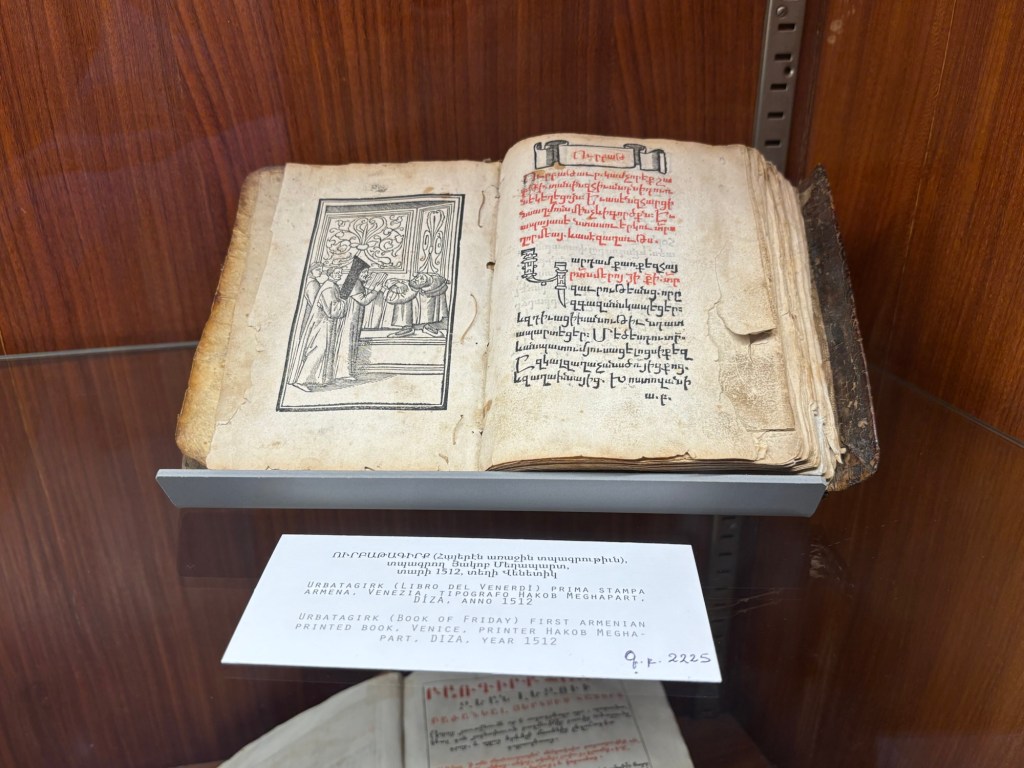

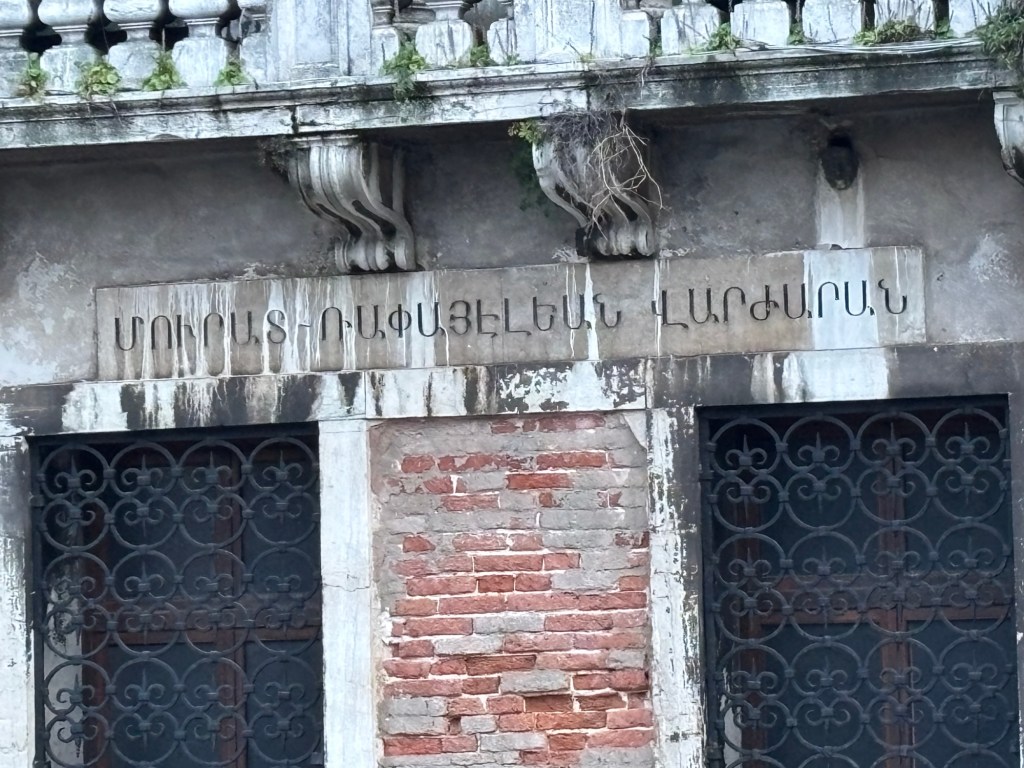

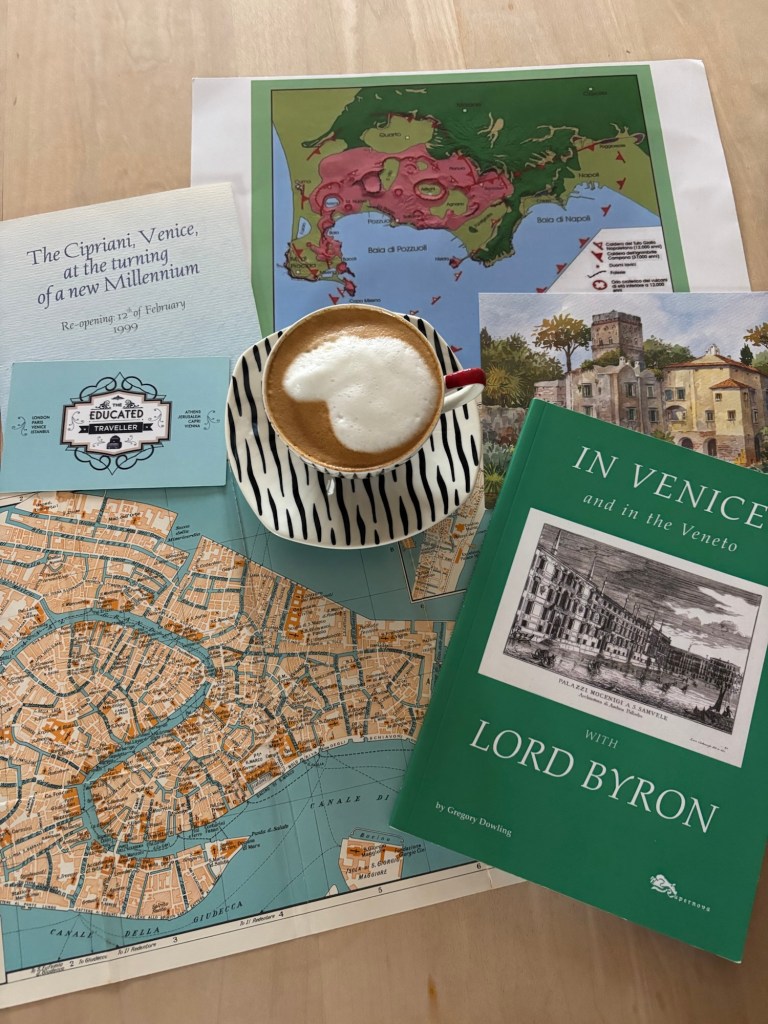

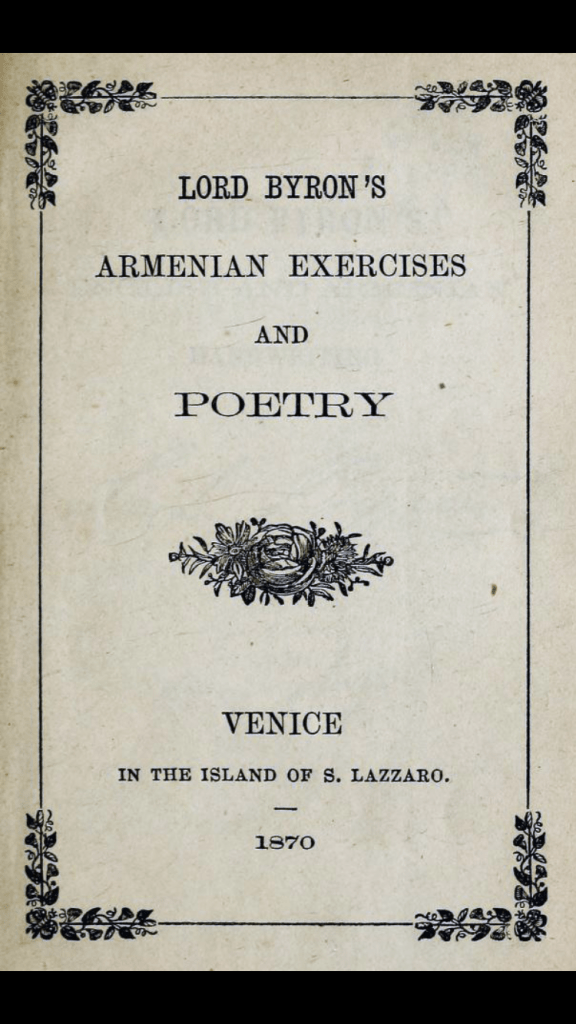

Venice is considered the birthplace of Armenian printing. An Armenian printer called Hakob Meghapart published the first Armenian book in Venice in 1512. The book known as ‘Urbatagirk’ or the Book of Fridays (pictured below) used a very specific Armenian typeface including the 39 letters of the Armenian alphabet. The book contains prayers, remedies for the sick, and a collection of mystical poems. Armenia was the first country to adopt Christianity as their official religion in 301 AD. This decision led to religious persecution over the centuries, especially during the Ottoman Empire. Venice became an important sanctuary for Armenians and printers like Hakob Meghapart were instrumental in preserving Armenian literature through printing books. Later in the early 18th century a charismatic Armenian priest Mechitar arrived in Venice and managed to persuade the Venetians to give him an island on which to establish a monastery. The island was San Lazzaro, an abandoned leper colony. The monks have remained there ever since. You can read more about the Armenians on San Lazzaro in an article I wrote here: The Armenian Island in Venice – San Lazzaro degli Armeni… One of the most famous visitors to San Lazzaro was the British poet Lord Byron, who spent many days on the island, as a guest of the monks in the winter of 1816-1817. He worked with one of the monks to write and then publish an English-Armenian Grammar Book. During the course of his stay Byron wrote to Mr Murray (his publisher in London) asking if there were Armenian type (faces) and letter-presses in existence in England, suggesting they might exist in Oxford or Cambridge. Interestingly to this day Oxford and specifically the Bodleian Library has one of the finest collections of Armenian manuscripts and books in Northern Europe. It is even possible to study Armenian Language and Literature at Oxford University. You can read more about Lord Byron and the Armenian island in Venice here: Lord Byron and the Armenians in Venice….

Cloisters, San Lazzaro, Book of Fridays (1512) centre. Armenian College, facade, Venice (detail).

Book of Fridays (detail) above – photo: www.educated-traveller.com

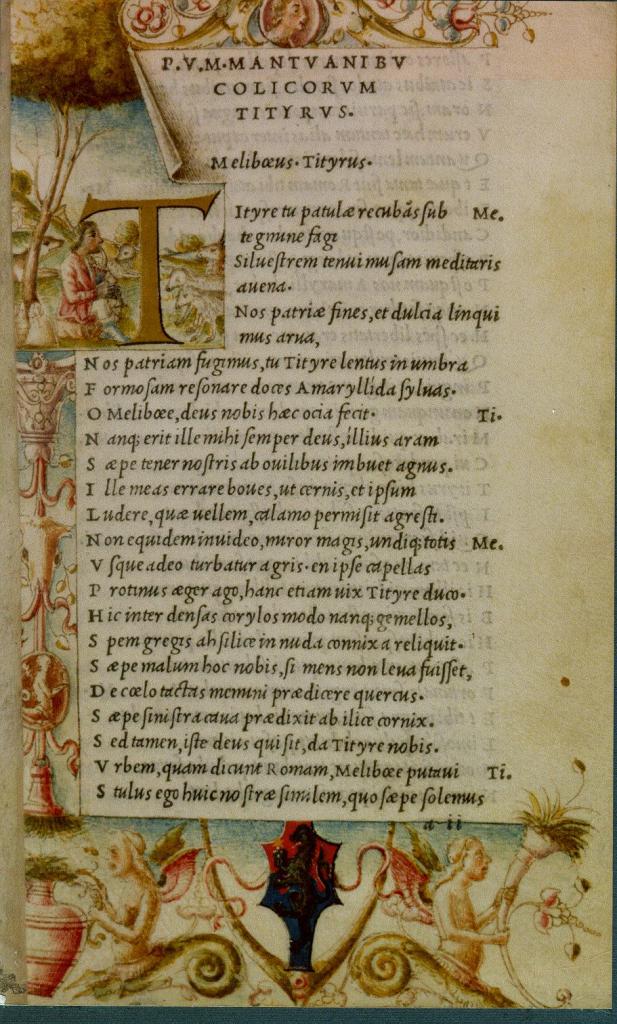

Venice – Studio of Aldus Manutius, 19th C interpretation by Francois Flameng (left). Aldine Vergil (1501) right – John Rylands Library Manchester

THE PRINTING REVOLUTION – Before the invention of the printing press books were written out by hand. These hand-written books were known as manuscripts, they were laboriously copied out by monks working in the ‘scriptorium’ or writing room of a monastery. When the printing press arrived the first books to be printed rather than hand-written were known as‘incunabula’. This term is used to refer to very early printed books, typically those printed between 1450 and 1500. These incunabula books were often large, folio size books designed to be read at a lectern or on a large table. They were heavy and usually kept in libraries or reading rooms. In 1501 Aldus Manutius produced his first ‘octavo’ pocket books. The name comes from the 8 pages created when large sheets of paper were folded three times to produce 8 small pages for printing. These books were small, light and easy to carry around. The photo above shows a page from the 1501 edition of Virgil’s poetry published by the Aldine Press in Venice. It is now in the John Rylands Library, Manchester.

The publishers and printers of Venice, people like Aldus Manutius and also Hakob Meghapart (the Armenian printer) were the arbiters of taste of their day. When they selected a manuscript or a book for printing they were effectively deciding which books and what writers were available to the reading public. When Manutius selected Francesco Petrarca’s poetry for publication in 1501, using the new italic typeface and the handy ‘octavo’ pocket book size, it was a huge success. One thousand copies were sold. A year later Manutius printed Dante’s ‘La Commedia’ again using italic typeface and the ‘octavo’ format. The ‘Commedia’ was the first book to include the now famous ‘dolphin and anchor’ printer’s mark. Both these books were printed in Tuscan dialect, the foundation of modern Italian. Imagine the delight of the reading public to discover a book that they could read which was not in Latin or Greek but in the ‘common’ vernacular language of the streets.

Last year in New York at a sale of Aldine books, Sotheby’s Auctioneers described Aldus Manutius and his print shop as ‘a small italian printing press that revolutionised reading in the renaissance’. I for one am inclined to agree.

Notes and Links:

- There’s still a tradition of printing and publishing in Venice. My friend Gianni Basso continues the tradition: Venice – a traditional printer at work his workshop is well worth a visit.

- I write about Byron’s fascination with the Armenians here: Lord Byron and the Armenians in Venice….

- Dante – Italy’s greatest poet

- Dante – an early manuscript from Biblioteca Guarneriana, Italy

- Italy – enchanted gardens story-telling and survival… – an article I wrote about Petrarca during Covid!

- Aldus Manutius was born around 1450 – he died in Venice in 1515. His printing office was in San Polo, Calle del Pistor.

- His Aldine Press left an indelible stamp (pardon the pun) on printing forever.

- Interesting context – on the value of the Aldine editions today. Sotheby’s Auction in New York, June 2025 featuring various Aldine texts. Sothebys – How a small Italian press revolutionised reading

- Above – Painting of Aldus Manutius (standing) with Jean Grolier (seated) is a late 19th century capriccio by Francois Flameng, held in a private collection in New York. Jean Grolier was a famous 16th century book collector and bibliophile.

- Stained glass window – above – shows Manutius & William Caxton, rendered in Tiffany Glass, Pequot Library, Southport (CT), USA

- Manutius quotation (in article) from Clemons, Fletcher (2015) ‘Aldus Manutius – A Legacy more lasting than bronze’ The Grolier Club, New York

- Meanwhile – William Caxton, printer and publisher working in Westminster, London – printed Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales in English in 1476 and again in 1483. The book was folio size and used a ‘Burgundian style’ of typeface. Caxton was a business man and chose the already popular Canterbury Tales because he wanted a book that was a commercial success.

Lord Byron’s association with the island of San Lazzaro and the monks printing traditions are fondly remembered.

February 2026