In the darkest days of the Second World War Jewish men and women were taken from their homes, often by force, and placed in prison camps. Weeks or months later they were transported to concentration camps in eastern Europe. These camps for many, were a place of no return….

27th January is ‘La Giornata della Memoria’ in Italy – a day to remember and a day to pay our respects. This day is vocally supported in Italy with numerous events and ceremonies scheduled from Trieste in the north to Puglia in the south. Rome, Torino, Ancona and Bologna all mark this important day. The Italian Jewish experience was unique and shocking. To this day it is a source of intense regret and sadness.

The Jewish community in Italy was an intrinsic part of Italian society. Jewish families had lived in Italy for generations. The Jewish Ghetto in Venice was the oldest in the world, dating from 1516, and in fact the name ‘ghetto’ comes from the foundry or iron works located next door to the part of the city where Jews were permitted to live. The original ghetto in Venice was a segregated community, guarded by Christian watchmen. Jews were permitted to leave the ghetto during the day, to work, but each evening at dusk, they were required to be inside the gates and a curfew was imposed. The people of the ghetto were locked in every night.

The Venetian approach to the Jewish community was contradictory and typically Venetian. On the one hand the Jews were obliged to live in the ghetto and were officially segregated from the rest of society, on the other hand Jewish people in Venice were important money lenders, doctors, tailors and teachers. Venice was a city of trade and merchants. Money was necessary to grease the wheels of commerce. Cash had to be raised to buy cargoes, pay customs taxes and purchase goods. Shakespeare’s character ‘Shylock’ is a Jewish money lender plying his trade at the Rialto in ‘The Merchant of Venice’. So whilst technically the Jewish community were segregated, in practical terms they were fundamental to Venice’s trading activities. The money lenders (mostly Jewish) provided access to capital enabling Venetian businesses to grow. This arrangement continued for centuries. It wasn’t until Napoleon came along in 1797 that the ‘ghetto’ was outlawed and the Jewish community were free to live wherever they chose. The reality was that many Jewish families stayed where they were, surrounded by family and friends in an environment that they knew and in which they felt secure.

In many other historic cities in Italy you can still see a section of the town that was once Jewish; Rome, Bologna, Ferrara, Ancona, Torino and even tiny Asolo (in the Venetian hills) had their Jewish districts. These neighbourhoods were often in the heart of the old town, medieval in their layout, with narrow alley ways and tall buildings giving a glimpse of the crowded living conditions that once existed. And so it continued for centuries, generation after generation of Jewish families lived and worked, married and died in Italy. Many Jewish families were eminent in the fields of medicine, law and teaching.

In the 1920s and early 1930s Fascism arrived in Europe. Mussolini, Italy’s famous leader, originally a Socialist, allied himself disastrously with Hitler and passed the infamous ‘Race Laws’ of 1938 which excluded Jewish people from Italian society and systemically deprived them of their rights as citizens. Justification for this terrible action came from a particularly nasty document known as ‘The Manifesto of Race’ a deeply tenuous pseudo-scientific paper produced by a group of right wing supporters of Hitler and Mussolini. Fearing for the future, many Jewish families left Italy from 1938-1942 often heading for a new life in the United States. Many were not able to leave, they didn’t have the financial means to move to another country. As the war progressed so the Jewish situation in Italy worsened. In fact the terrible tragedy for many Italian Jews is that they were removed from their homes and deported to concentration camps like Auschwitz in the final months and even weeks of the war.

In Ferrara, where there’d always been a dynamic and fully integrated Jewish community, families were being deported in 1943 and 1944, whilst the Allied Forces were making their way north through Italy. It strikes me as heart-breaking that Jews were being arrested and interned within months of Italy’s liberation. The fact that British, American and Canadian troops were making their way north through the Italian peninsula and literally an hour or two to the north German soldiers were rounding up Italian Jews and putting them on trains, never to return, sums up the brutality and cruelty of war.

The novelist Giorgio Bassani wrote a fantastic book about an aristocratic Jewish family living in Ferrara, called the Finzi Contini. In his book this educated, civilised, elegant family nearly survive the war. It makes for tearful reading: Ferrara and Giorgio Bassani. The photos below show the idyllic and peaceful Jewish cemetery in Ferrara. The premise of Bassani’s tale is that the Finzi Contini tomb is empty because the family members were deported to Auschwitz in December, 1944 – just five months before the end of the war. If you find yourself in Ferrari visit the Jewish cemetery, it’s a beautiful and peaceful place and not as melancholy as you might expect. The Finzi Contini family are now the subject of a brand new opera which will premier tonight (27th January, 2022) in the Folksbiene Theatre in New York – I wish the cast well.

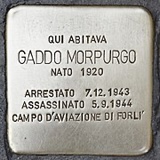

How is it possible for a country, a territory, a people to commemorate a tragic series of events that happened just a few generations ago. On the one hand we want to forget, we are sad, angry, even embarrassed, on the other hand we understand the importance of history and want to learn from our mistakes….. A German artist called Gunter Demnig came up with an ingenious solution in the 1990s. He created a small permanent memorial for the victims of the holocaust, a very personal memorial. His idea was to create a cobble stone, roughly 10 cm by 10 cm with a brass capping. On the brass plaque the details of a holocaust victim are engraved. These stones are then embedded in the pavement outside the individual’s last ‘freely chosen’ residence. These stones are known as ‘stolpersteine’ in German, which translates into English as ‘stumble stones‘ whilst in Italian they are called ‘pietre d’inciampo’. These simple, shining, reflective memorial stones are appearing in towns all over Europe as a poignant reminder of what happened to so many Jewish people in those terrible years.

The ‘pietro d’inciampo’ to the left (above) commemorates Ferruccio Ascoli born in Ancona, 1897 and arrested on 27th April, 1944. He was deported to Auschwitz where he was put to death on 30th August, 1944. Ferruccio bears the family name Ascoli, a well known town and regional centre in Le Marche. It was common for Jewish families arriving in Italy in medieval times, often fleeing persecution, to take the name of the town that they first lived in as their surname. So we can infer that Ferruccio Ascoli’s family originally settled in Ascoli.

In Italy the ‘pietre d’inciampo’ have been enthusiastically welcomed.

Each of these brass-capped stones is engraved with the same details. The name of the person, date of birth, the date of their arrest and their ultimate fate. A small and yet deeply poignant life story lies within these stark details. In the photos above you can see the stone dedicated to Estella Stendler, a pastor’s wife from Pordenone who was imprisoned at the Risiera di San Sabba, in April 1944. San Sabba was famous as being the only extermination camp on Italian soil, a huge, cavernous former rice factory, located on the edge of the city of Trieste. The last line of Estella’s stone says, ‘Destino Sconosciuto’ destination unknown. The photo below shows the stones representing the Todesco family – six people in total, who lived in the Jewish ghetto in Venice. The parents, mother and father, both 46 years of age, their children, all boys, aged 17,16,10 and 5. Shipped to Buchenwald and Auschwitz. Emilio, the 16 year old died two months before the war ended in March, 1945. Just eight more weeks and he might have survived. The war ended in May, 1945.

I’m reminded of the brutal but accurate wall plaque in the Jewish cemetery at Ferrara which states, rather joylessly:

- ‘….Polvere sei e alla polvere tornerai…’

- Ashes you are and to ashes you will return……………………….

On this day of ‘Memoria’ in Italy it seems more important than ever that we remember with humility and respect those that went before us and the gift of life that we all currently enjoy.

Notes:

- The ‘stolpersteine’ project originated in Germany (Cologne) in the early 1990s. The idea of Gunter Demnig – a German artist (pictured below).

- The ‘stolpersteine’ have been enthusiastically adopted in Italy. Springing up all over: Venice, Ferrara, Rome, Trieste…..Many cities are also producing maps to show the location of the ‘stolpersteine’

Here the region of Emilia Romagna explains the purpose of the ‘stolpersteine’ in Italian:

- Emilia Romagna – La lista delle pietre d’inciampo in Emilia-Romagna contiene l’elenco delle pietre d’inciampo (in tedesco Stolpersteine) poste in Emilia-Romagna. Esse commemorano le vittime della persecuzione del regime nazista nell’ambito di un’iniziativa dell’artista tedesco Gunter Demnig estesa a tutta l’Europa. La prima pietra d’inciampo in Emilia-Romagna è stata collocata a Ravenna il 13 gennaio 2013. Al 2021 le Stolpersteine in Emilia-Romagna sono 168.

- Le Marche region have stones in Ancona and Ostra Vetere. Here’s what they have to say:

- Generalmente, le pietre d’inciampo sono posizionate di fronte all’edificio dove le vittime hanno avuto la loro ultima residenza autogestita. Le prime pietre d’inciampo in questa regione sono state collocate il 12 gennaio 2017 ad Ancona ed Ostra Vetere.

- Whilst in Torino they report: L’iniziativa è partita a Colonia nel 1992 e ha portato, a inizio 2019, all’installazione di oltre 71000 “pietre” in tutta Europa. La cinquantamillesima pietra venne posata a Torino e con le pose di quest’anno saranno presenti nel territorio cittadino 114 pietre.

I’ve written various articles about Italy, the Jewish community and Ferrara. You may enjoy:

- Ferrara – a perfect, small city in Italy

- La Custode – The Guardian

- La Vita e Bella – Life is Beautiful (1997)

- Ferrara and Giorgio Bassani

- The Leopard and other exceptional Italian Films…

LASTLY – The Folksbiene Theatre Company in New York are currently premiering a brand new opera ‘The Finzi Contini’ inspired by the Jewish family in Giorgio Bassani’s novel. Here’s the link to buy tickets, several dates are already sold out https://nytf.org/finzi-continis/

Written: 20th January, 2022

A fantastic project – Freiburg (Germany) has many stolpersteine too – a daily reminder of the people taken from their homes and never to return, yet not forgotten.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely Shona – funnily enough there’s one German city that is not keen on the stolpersteine – can you guess which one?

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a wonderful but such a sad story, Janet. Thank you for telling it.

LikeLiked by 1 person