In the days before the camera, skilled artists were often required to record important events. It was their job to paint a canvas that not only looked professional and interesting but also could be used as a reference point in the future. Cesare dell’Acqua was such an artist. The purpose of this article is to discuss and examine the ways in which paintings can record historical events.

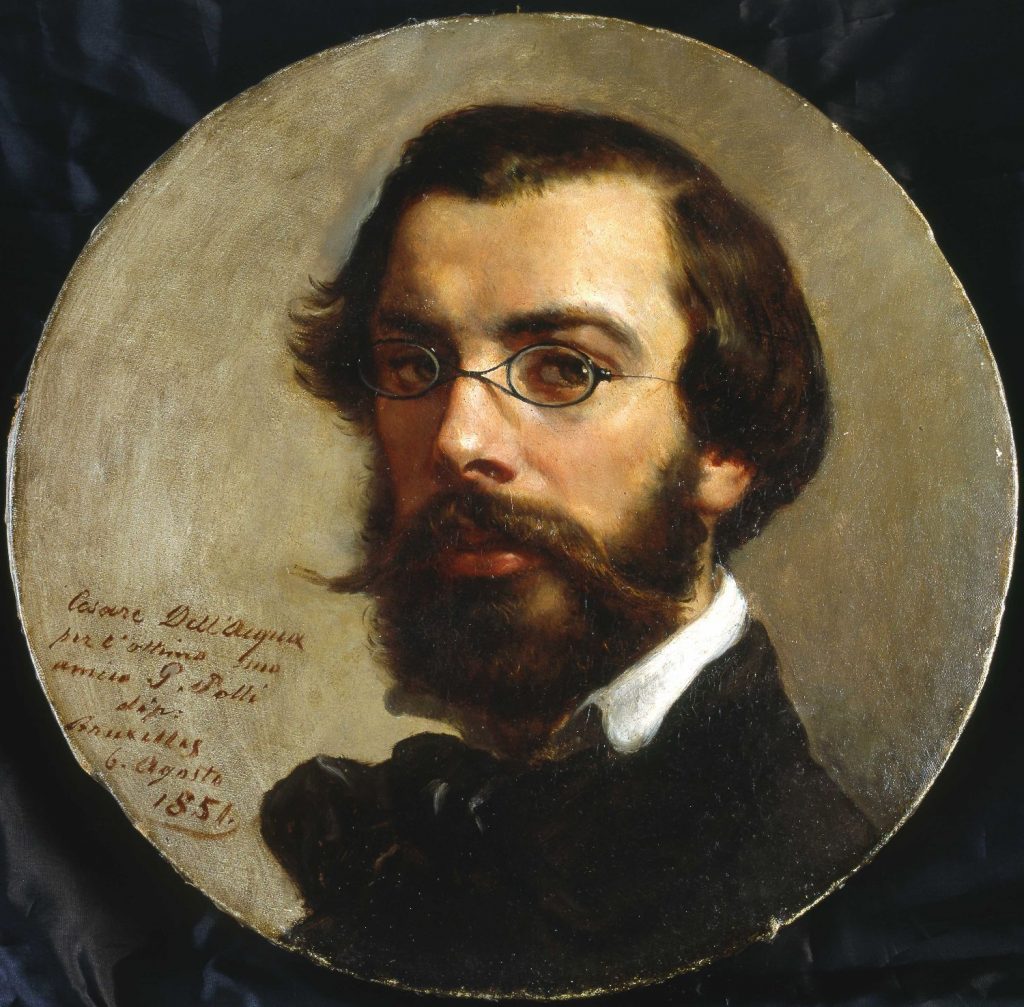

Cesare dell’Acqua (1821-1905) was a talented painter working in Trieste in the middle years of the 19th century. At that time the city of Trieste was part of the Austrian Empire. Cesare was born in the small town of Pirano, about 30 kms south of Trieste. He trained as an artist in Capodistria, Trieste, Venice and Brussels. His detailed painting style and rich use of contrasting colours as well as his almost photographic attention to detail made him a favourite of Maximillian, younger brother of Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria. I’ve chosen dell’Acqua’s painting ‘The visit of Empress Elisabeth of Austria to the Castello of Miramare, 1861’ to make my point.

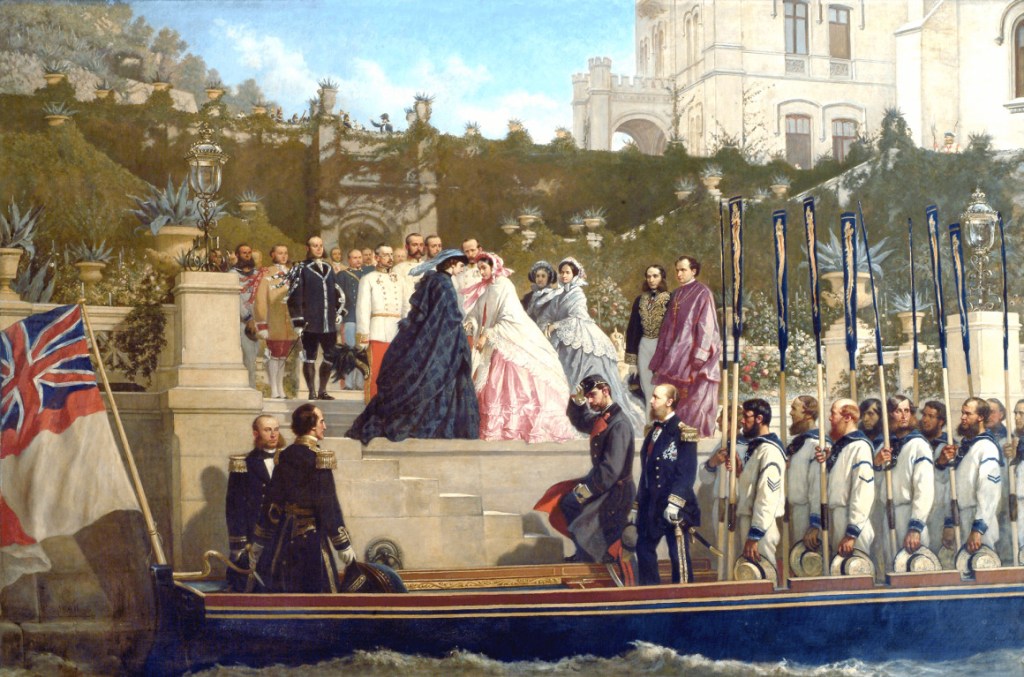

The painting below shows the Empress Elisabeth of Austria arriving at Maximilian’s idyllic, waterfront palace, known as Miramare Castle in 1861. She is being welcomed to the castle by Charlotte, Maximilian’s wife. Charlotte is wearing a rose coloured dress with a white shawl whilst Elisabeth is dressed in a rather more sombre navy blue dress and shawl. Both women have hats that co-ordinate with their gowns. A pink bonnet with ribbons for Charlotte and a blue hat with pale blue feathers for Elisabeth. The women greet one another fondly, they are sisters-in-law.

Still on the boat, are the two most important men in the Austrian Empire, the Emperor and his younger brother Maximilian. They are preparing to disembark. Emperor Franz Joseph is dressed in a grey military trench coat and cap. He thanks the officers for his safe passage. Meanwhile Maximilian is dressed in navy blue, and is wearing an admiral’s uniform. He is the Commander-in-Chief of the Austrian Navy.

The royal visitors have arrived on a Royal Navy (British) tender which has been rowed to the small private dock at Miramare Castle by a crew of at least ten mariners. The rowers stand to attention, oars held high, and hats removed, as they respectfully watch the departure of their VIP guests. The British flag, the ensign flies in the stern of the boat, whilst the disembarkation process is supervised by two high ranking naval officers. My first question on viewing this picture was, Why are the Austrian Imperial family arriving at Miramare in a boat flying the British flag?

The answer is quite simple. In 1861 Queen Victoria of England had loaned her own private yacht ‘HMY Victoria and Albert’ to Franz Joseph of Austria and his wife Elisabeth, as a show of friendship and generosity. The royal couple were able to cruise the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas under the protection of the British Navy. In the 1860s, the British presence in the Mediterranean was very significant. Construction had begun on the Suez Canal project and the British Navy were very keen to keep London’s investment in the eastern Mediterranean secure. Also, and I love this detail, Queen Victoria was very fond of Franz Joseph, in him she saw a fellow monarch of similar standing to herself. In fact Victoria ruled the British Isles and the Empire for 64 years whilst Franz Joseph managed the Austro-Hungarian and later the Austrian Empire for 68 years – quite a feat.

The visit of Empress Elisabeth of Austria to Castello di Miramare, 1861 – Cesare dell’Acqua, painted 1865

Back on dry land, the staff of the castle and the ladies-in-waiting to Charlotte watch proceedings and form a welcome party. Several other Austrian naval officers are partially hidden from view by the ladies, as they greet one another. The officers are all wearing the cream jacket and red trousers of naval officers. In the background the beautiful terraced gardens of Miramare Castle appear, fairytale like, coated in verdant green creepers and climbers. The main entrance to the castle is visible in the top right quadrant of the painting. This painting hangs in the ‘Sala di Cesare dell’Acqua’ the painting gallery at Miramare Castle. It’s a statement asserting Austrian military power on this part of the Adriatic coastline, at a time when the power of the Habsburg dynasty was already under serious threat.

So what does this painting tell us. It tells us that the Emperor of Austria and his very popular wife Elisabeth, visited Maximilian and Charlotte at Miramare Castle. The meeting looks joyful and happy. It shows us a gorgeous garden at Miramare, filled with beautiful plants. It shows us two women, meeting and exchanging greetings. It shows us a happy picture. A canvas of tranquility and order. However, the 1860s were a turbulent decade in Europe. The Austrian Empire was being threatened on all sides. To the south the newly created kingdom of Italy was founded in 1861 with King Vittorio Emanuele II at the helm. In the east the Hungarians were demanding independence, whilst to the north the Prussians were consolidating their position as a dominant German state, at the expense of the Austrians. Nationalism was in the air. No wonder the Emperor and Empress accepted Victoria’s kind offer of her own private yacht.

Cesare dell’Acqua painted numerous canvases for Maximilian, many of which still hang at Miramare Castle. The most poignant of which is the ‘Delegation from Mexico’ offering Maximilian the crown of Mexico. This ‘offer’ was a poisoned chalice. Nobody had consulted the Mexicans on who they would like as their ‘Emperor’. Poor old Maximilian accepted the invitation, set sail for Mexico with Charlotte, leaving his beloved Miramare Castle forever. He arrived in Mexico in June 1864, three years later he was shot dead by the independence fighters of Benito Juarez. Poor Max. He didn’t stand a chance. In the painting below Cesare dell’Acqua captures perfectly the solemnity of his meeting with the Mexican delegation, as they requested his presence as the next Emperor of Mexico. Note the chandelier, with its numerous crystal beads and flutes (almost certainly made by hand in the glass workshops of Bohemia). Does the chandelier hang above the heads of the delegates as a metaphorical ‘sword of Damacles’ indicating the deeply flawed invitation and it’s inevitably gruesome end.

The Mexican Delegation arrive at Miramare to offer the crown of Mexico to Maximilian (1863)

To complete the hat trick – yet another canvas of Cesare’s below, is the rather sombre and sad departure of Maximilian and Charlotte from Miramare in June 1864. The artist has filled the painting with bluster and bravado. Crowds fill the breakwater to wave off the hero. The menacing tone of the painting is a deliberate device by the artist. There is a funereal air to the costumes of Maximilian and Charlotte, standing in the boat ready to be rowed out to their ship. They will arrive in Mexico in 1864. By 1867 Maximilian was dead, executed by independence fighters in Mexico led by Benito Juarez.

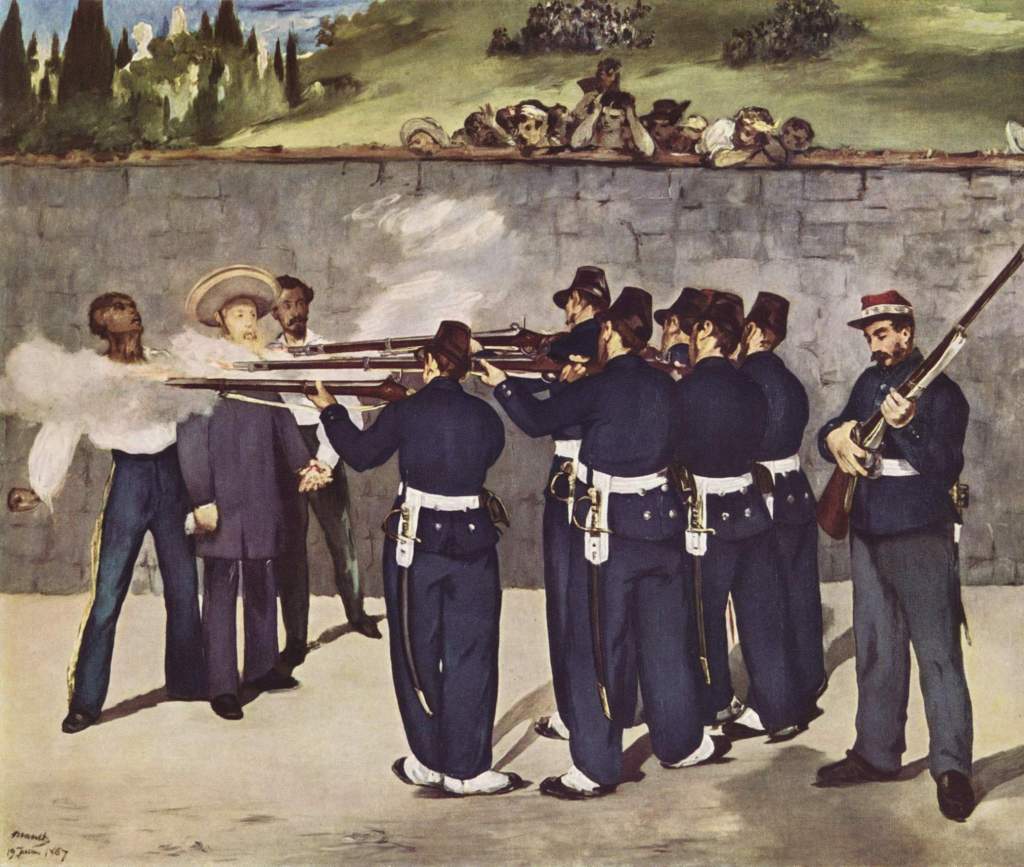

Now we’ve come full circle, the execution of Maximilian in Mexico became the subject of a series of paintings by Edouard Manet. The version below is in the Kunsthalle in Mannheim in Germany. Manet was a modernist painter, he painted real life, he painted battlefield scenes, picnics in the park and days at the races. His series of paintings depicting in graphic detail the shooting of Maximilian, Emperor of Mexico, fascinated and horrified the ruling classes of Europe. In France the painting was forbidden – it was regarded as seditious. Freedom and independence were the twin moods of the day, on both sides of the Atlantic.

Execution of Emperor Maximilian, June 1867 by Edouard Manet (Kunsthalle, Mannheim)

Of course the painter and the ideas of the time influence the content and theme of each individual painting. Artists are influenced by the politics of the times, they are influenced by their teachers and mentors. Cesare dell’Acqua was influenced by his powerful patron (Maximilian) and his role effectively as the Austrian Court Painter in Trieste. In the 1860s it was Cesare’s job to record the key events of Austria’s littoral, he left behind a compelling record that is fascinating to investigate. So next time a painting catches your eye, stop and look at it, carefully. You’ll be amazed at the detail and information it can reveal.

Miramare Castle and harbour (left and centre), Cesare dell’Acqua – Self portrait of the artist, 1851 (right)

A NOTE ABOUT THE AUTHOR – Janet Simmonds is the Director of Grand Tourist a specialist travel company that offers exceptional journeys in Italy, France and the shores of the Mediterranean. The guiding principal of www.grand-tourist.com is to enable discerning clients to “rediscover the art of travel”. She is a graduate of the University of Oxford and holds a Master’s degree in the ‘History of Art’ from Manchester University.

She also writes a blog about travel www.educated-traveller.com

Further reading:

- Trieste – Italy

- Trieste – Miramare Castle and Maximilian

- Explore www.educated-traveller.com for hundreds of articles about Italy, The Alps, Mediterranean.

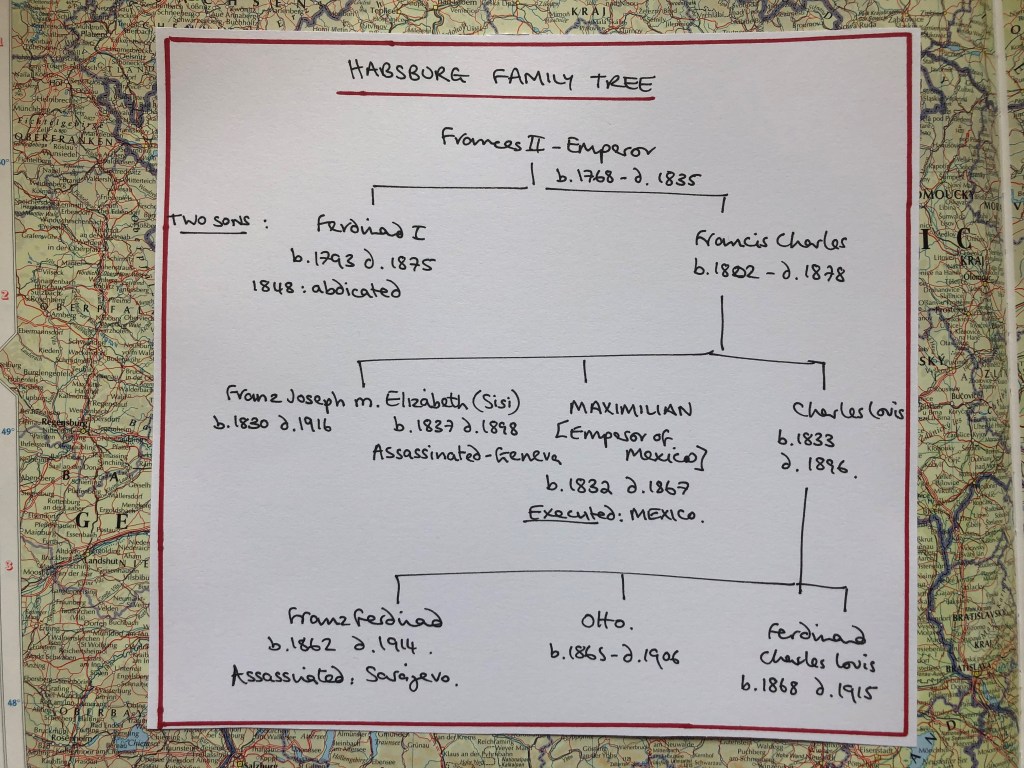

- The woes of the Austrian royals were only just beginning in the 1860s (see below)!

Habsburg Family Tree (left) inspired by The Guardian, 1914. Assassination of Elisabeth, Geneva, 1898 (centre). Finally the assassination of Franz-Ferdinand and Sophie, Sarajevo 1914 (right).

22nd Sept, 2025

Hi, Janet

Yet another note of thanks and congratulations on producing such an informative and fascinating piece. The mid-19th Century was a fascinating time, and there was so much happening in all the different “worlds” – historically, politically, militarily, musically, artistically and socially – and you have chosen a subject which embodies all of these, and with your usual ability to highlight the relevant detail to us otherwise somewhat ignorant readers!

I wasn’t previously really familiar at all with the works of Cesare dell’Acqua, and was most interested to read your account of his role and importance as a recorder of the major events of the day.

Just as an aside, it is interesting to see from the first picture (the visit of the Empress Elisabeth to the Castello di Miramare), that, although Maximilian was younger than his Brother the Emperor, in the picture, his balding head and older face makes him look by far the older of the two Brothers! (Point of Semantic interest – what is the difference between “older” and “elder”? Why do we refer to “Pliny the Elder” but say that “he looks older than his Brother” – is it that “older” is only used in comparatives?!)(And why, if it is “comparison” with an “I”, why isn’t it “comparitives” instead of “comparatives”? English is such a frustrating language, innit?!)

Thank you again for a really interesting read!

ATB

John

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you John – your comments are really appreciated. J x

LikeLike